Le présent rapport rend compte des principales activités, réalisations et impacts de l’association Russie-Libertés au cours de l’année 2025.

Fondée en 2012, Russie-Libertés est une association loi 1901 basée à Paris, engagée dans le soutien à la société civile russe et à celles et ceux qui défendent les droits humains, la liberté d’expression et les valeurs démocratiques, en Russie comme en exil.

Depuis sa création, l’association agit comme un acteur de médiation et de facilitation internationale, en établissant des passerelles durables entre la société civile russe, les institutions européennes, les organisations internationales, les décideurs publics et les acteurs de la société civile en Europe. Russie-Libertés œuvre à renforcer la compréhension mutuelle, à structurer le dialogue et à favoriser l’intégration des voix de la société civile russe dans les débats européens sur les droits humains, la paix, la sécurité et la démocratie.

L’action de Russie-Libertés repose sur une approche globale et complémentaire, combinant:

- le soutien direct aux activistes, journalistes, artistes, défenseurs des droits humains et personnes persécutées ;

- le renforcement des capacités professionnelles et organisationnelles des initiatives de la société civile en exil ;

- la coordination et la structuration de réseaux transnationaux d’acteurs engagés contre la guerre, la répression et l’autoritarisme ;

- un travail continu de plaidoyer auprès des institutions européennes et nationales afin de promouvoir la protection des populations vulnérables, la défense des libertés fondamentales et la reconnaissance du rôle de la société civile russe indépendante.

À travers ses projets, ses campagnes et ses espaces de dialogue, Russie-Libertés contribue à faire émerger une plateforme de coopération européenne autour des enjeux liés à la Russie contemporaine, en particulier dans le contexte de la guerre contre l’Ukraine, de l’intensification de la répression politique et de la fragmentation des acteurs civiques.

En 2025, l’association a poursuivi et renforcé son rôle de référence européenne pour la société civile russe en exil, en articulant action communautaire, plaidoyer international, mobilisation culturelle et production de connaissances, tout en affirmant sa mission de long terme : soutenir une société civile libre, résiliente et capable de contribuer à un avenir démocratique.

Les activités de l’association ont permis de contribuer à la place majeure de la France dans le processus de paix, au renforcement de sanctions efficaces, au soutien de la France à la société civile russe (la France étant le seul pays aujourd’hui à poursuivre la délivrance de divers visas à un grand panel de demandeurs russes, ainsi qu’à octroyer l’asile).

Projets phares de 2025

1. Forum Russie-Libertés 2025

- Objectif : dialogue entre société civile russe et acteurs européens

- Activités : panels, ateliers, concerts, keynotes (Monetochka, Yulia Navalnaya)

- Chiffres : 300+ participants, 25+ intervenants, collecte de 1 400 € pour Energy for Life

- Impact : visibilité médiatique, renforcement réseaux, échanges avec les institutions françaises et européennes

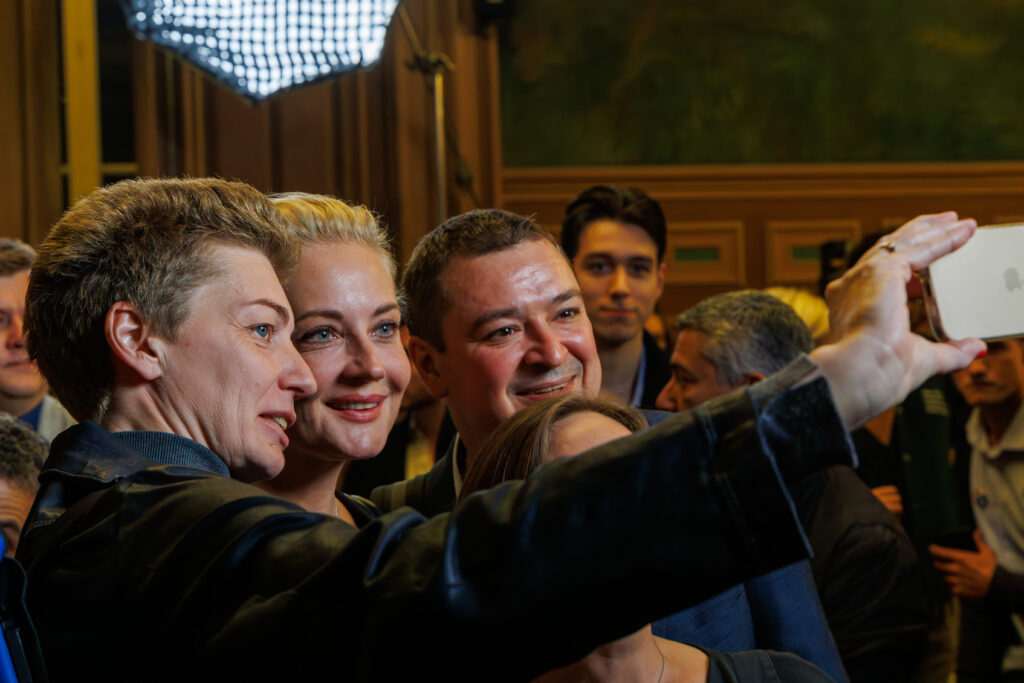

Le Forum Russie-Libertés 2025, événement phare de l’association, s’est tenu le 11 octobre 2025 à Paris. Il a réuni des responsables politiques français et européens, des représentants de la société civile russe, ainsi que des figures de l’opposition démocratique, afin de réfléchir collectivement à la guerre en Ukraine, à l’intensification de la répression en Russie et aux perspectives démocratiques.

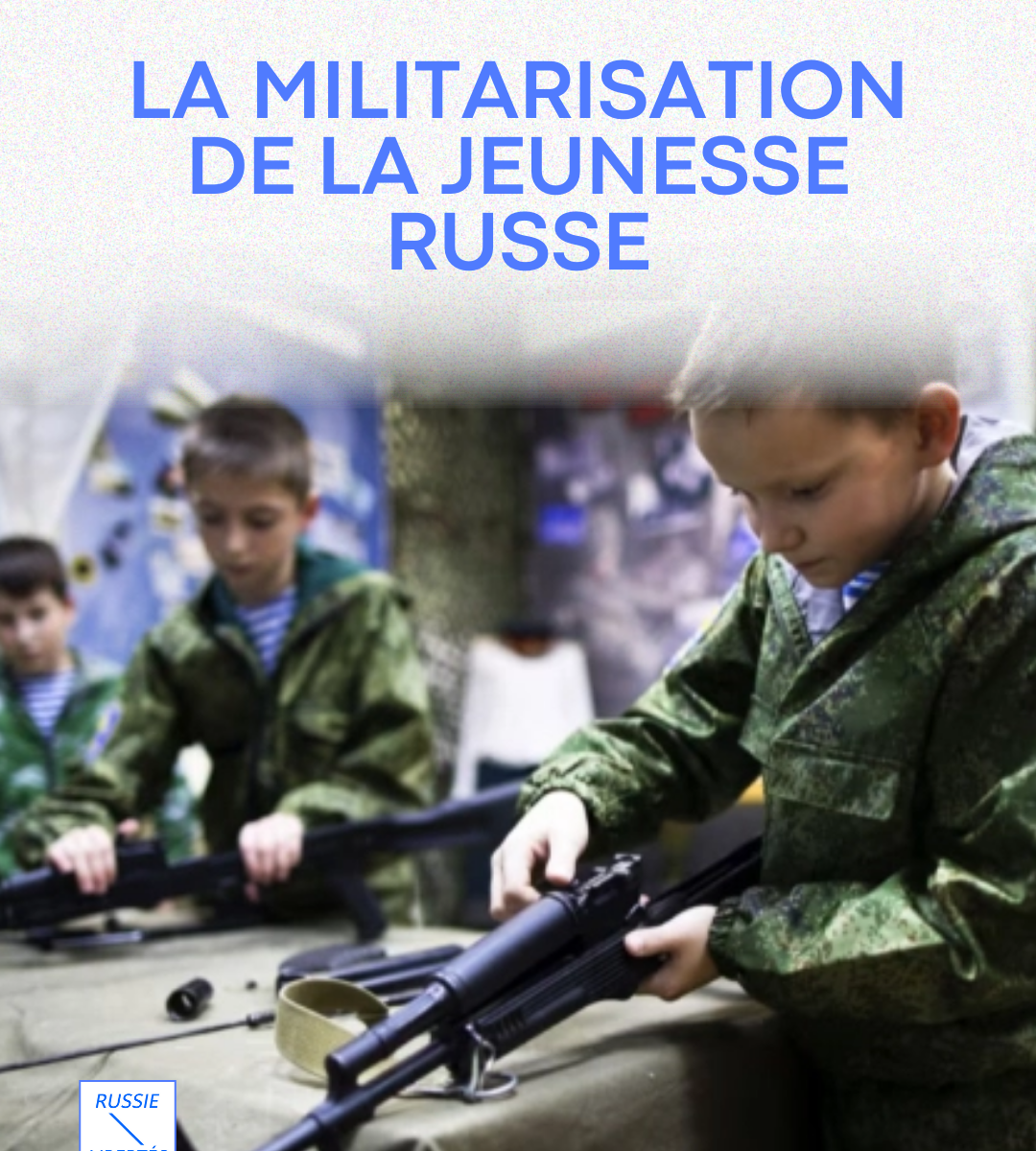

L’édition 2025 a rassemblé plus de 300 participants et plus de 25 intervenants lors de tables rondes et d’ateliers. Parmi eux figuraient notamment Elena Kostyuchenko, Oleksandra Romantsova (Center for Civil Liberties), Sergey Parkhomenko, Ksenia Fadeeva, ainsi que de nombreux experts, journalistes et militants. Les échanges ont porté sur les effets sociaux de la militarisation de la société russe, les enjeux de justice pour l’Ukraine, les défis auxquels fait face la société civile russe et l’impact de la répression sur la population.

Une attention particulière a été accordée aux campagnes de désinformation russes en Europe, à la propagande intérieure, ainsi qu’à la présentation de nouveaux projets médiatiques russes en exil, désormais accessibles en langue française, portés notamment par Novaya Gazeta Europe et The Bell Pro.

L’un des moments forts du Forum a été la participation de l’artiste pop russe Monetochka, dont l’intervention, mêlant échange public et performance musicale, a incarné une forme de résistance culturelle contemporaine. La journée s’est conclue par une allocution de Yulia Navalnaya, adressée à la communauté russe anti-guerre, marquant une nouvelle étape dans le dialogue et la coopération entre activistes russes et partenaires internationaux.

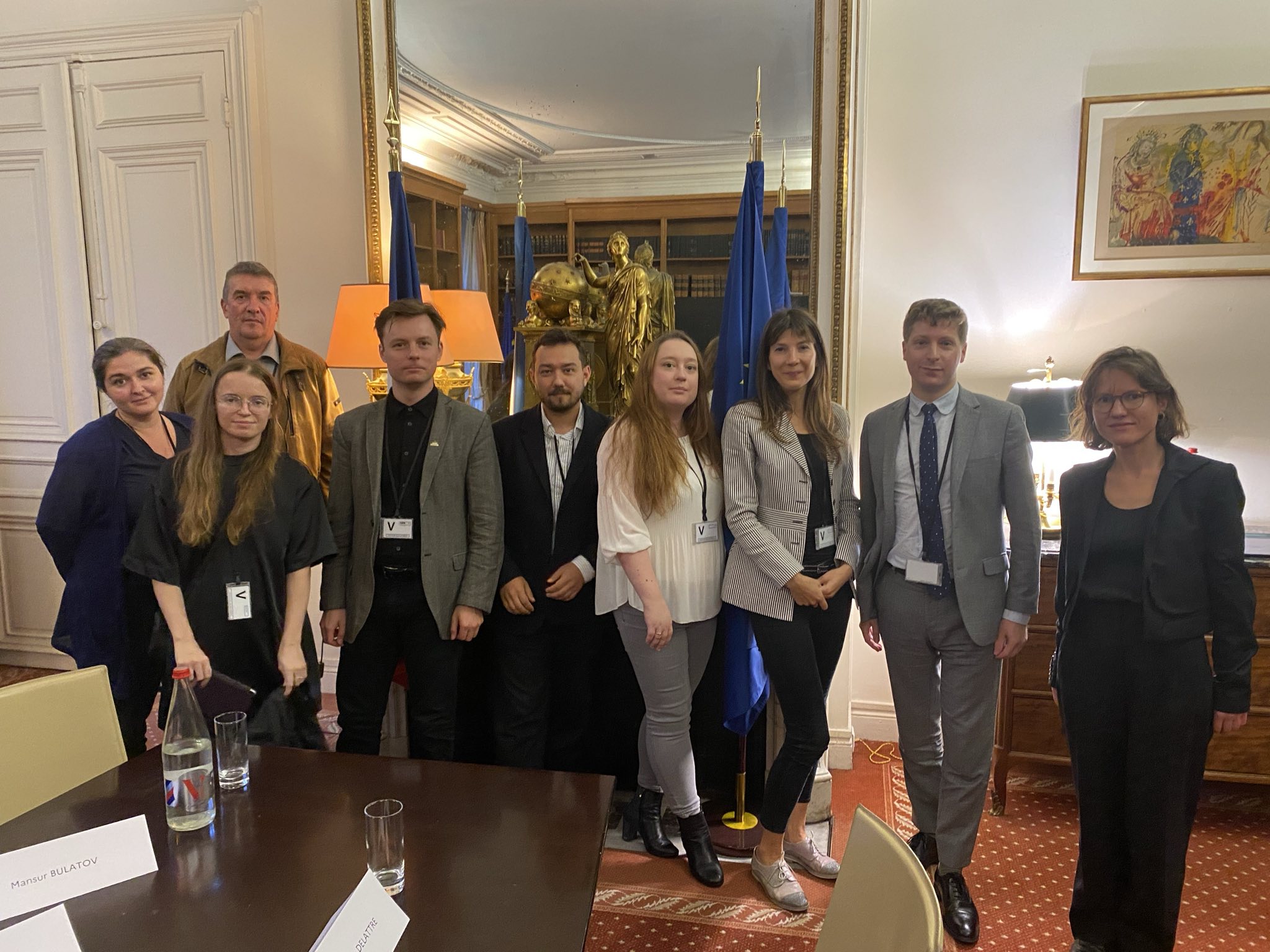

Au-delà des échanges publics, le Forum a également été un espace d’action concrète. Il a permis de collecter 1 400 € au profit de la campagne Energy for Life, destinée à soutenir les populations ukrainiennes touchées par les coupures d’électricité liées à la guerre. Par ailleurs, 25 activistes venus de différents pays européens et de Russie ont participé à des sessions de travail à huis clos, organisées en collaboration avec des collectifs iraniens, afghans et ouïghours basés à Paris. Ces rencontres ont été complétées par une réunion au Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, favorisant un dialogue direct entre acteurs de la société civile et institutions européennes.

Le Forum a bénéficié du soutien de nombreux partenaires institutionnels et associatifs, parmi lesquels la Ville de Paris, la Mairie du 11ᵉ arrondissement, l’Institut français, Amnesty International France, le gouvernement du Canada, Reporters sans frontières, l’association Pour l’Ukraine, pour leur liberté et la nôtre !, la Plateforme des initiatives civiques et anti-guerre, ainsi qu’Espace Libertés | Reforum Space Paris.

Parmi les intervenants figuraient également François Vauglin, maire du 11ᵉ arrondissement de Paris, Brice Roquefeuil, directeur pour l’Europe continentale au ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, et Geneviève Garrigos, conseillère de Paris. Leurs prises de parole, combinées à une programmation médiatique de haut niveau, ont créé un espace de dialogue particulièrement riche et mobilisateur.

Le Forum a donné lieu à de nombreuses interviews, contribuant à renforcer la visibilité de la société civile russe auprès du grand public.

Fort de cette dynamique, Russie-Libertés prépare d’ores et déjà l’édition 2026, avec l’ambition d’élargir encore la participation et d’approfondir les coopérations transnationales. De nouveaux axes de travail — notamment autour des droits numériques, de la liberté des médias et du soutien aux prisonniers politiques — viendront renforcer un réseau démocratique transnational fondé sur la solidarité, la résilience et la défense des droits humains.

Photos par Nikita Mouraviev et Ilya Zavialov

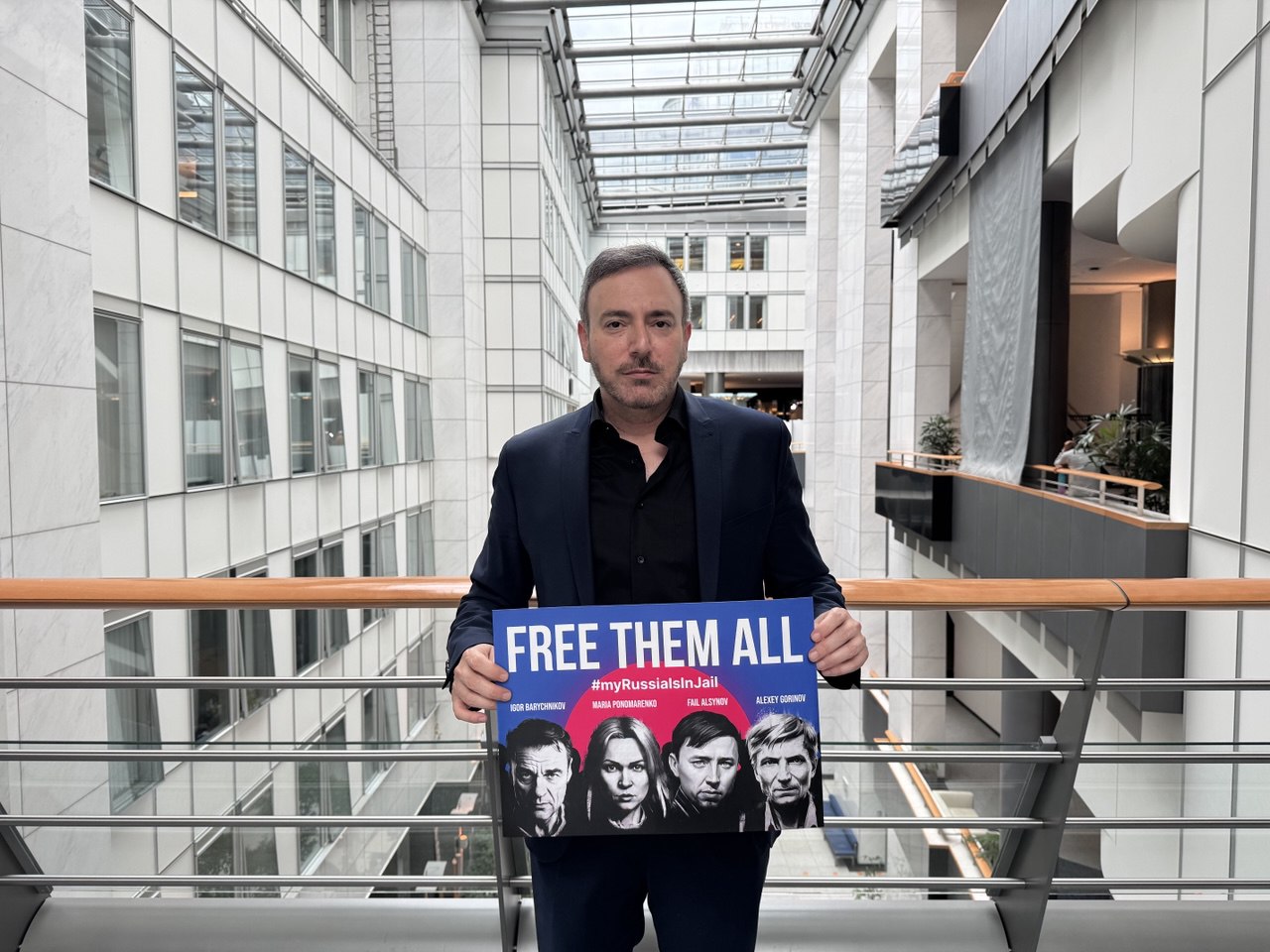

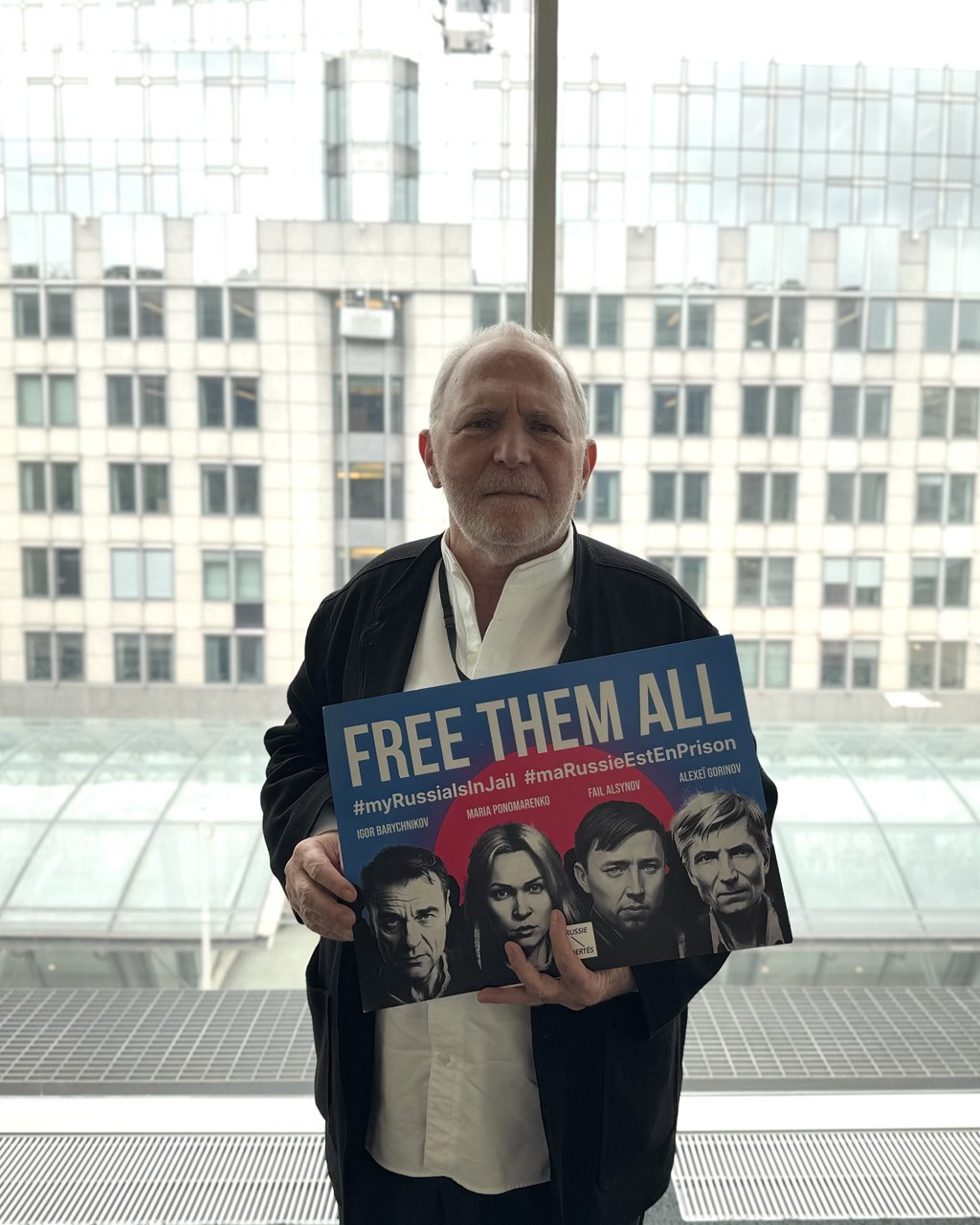

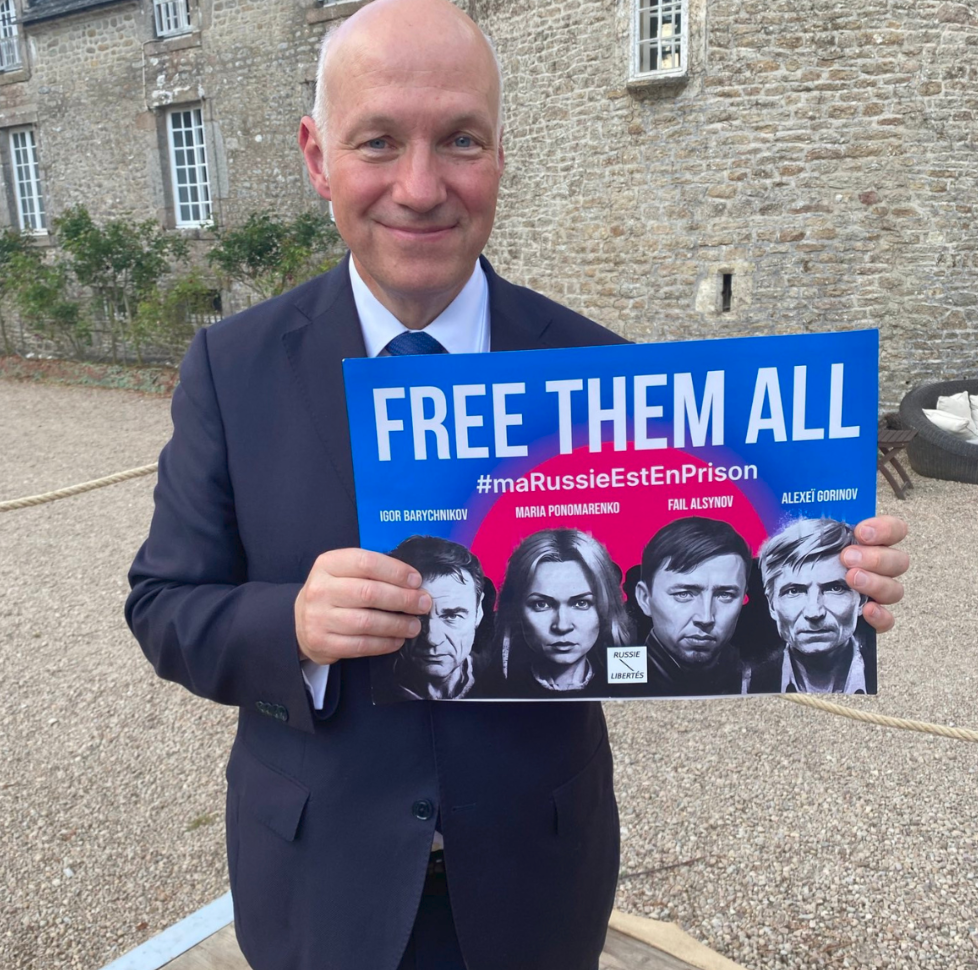

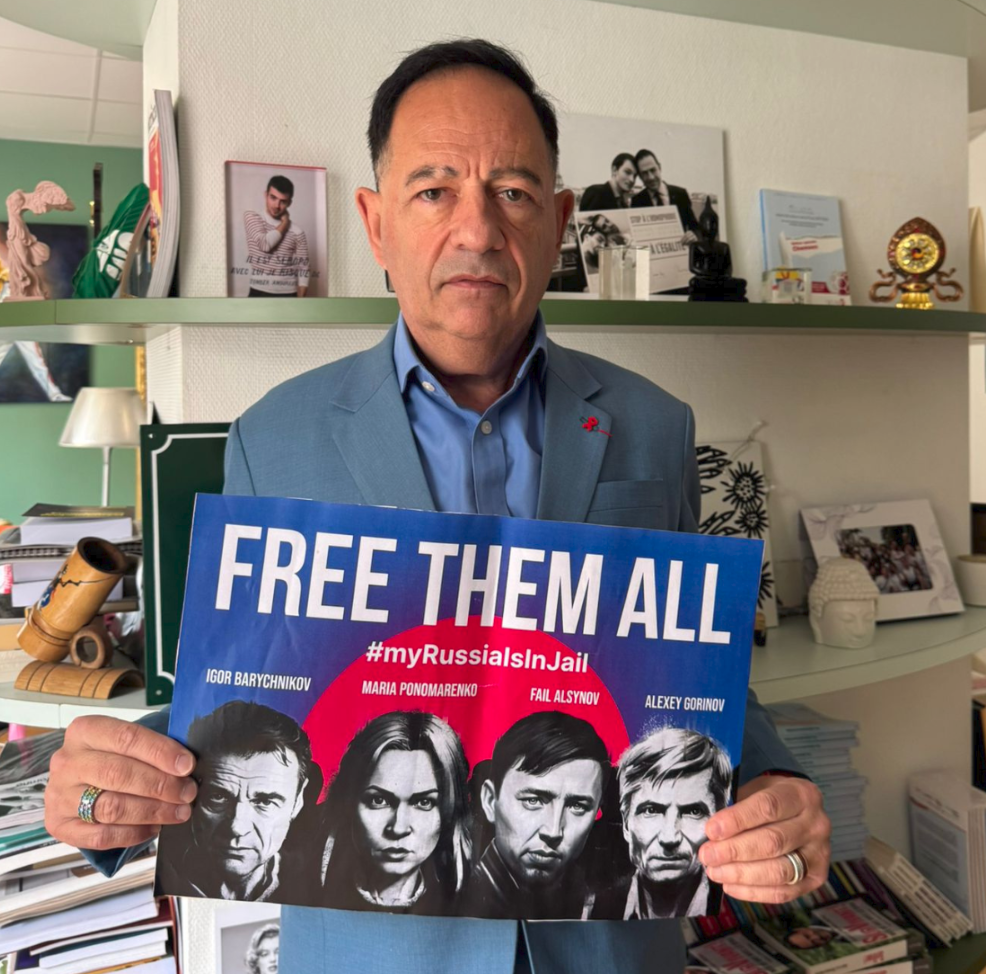

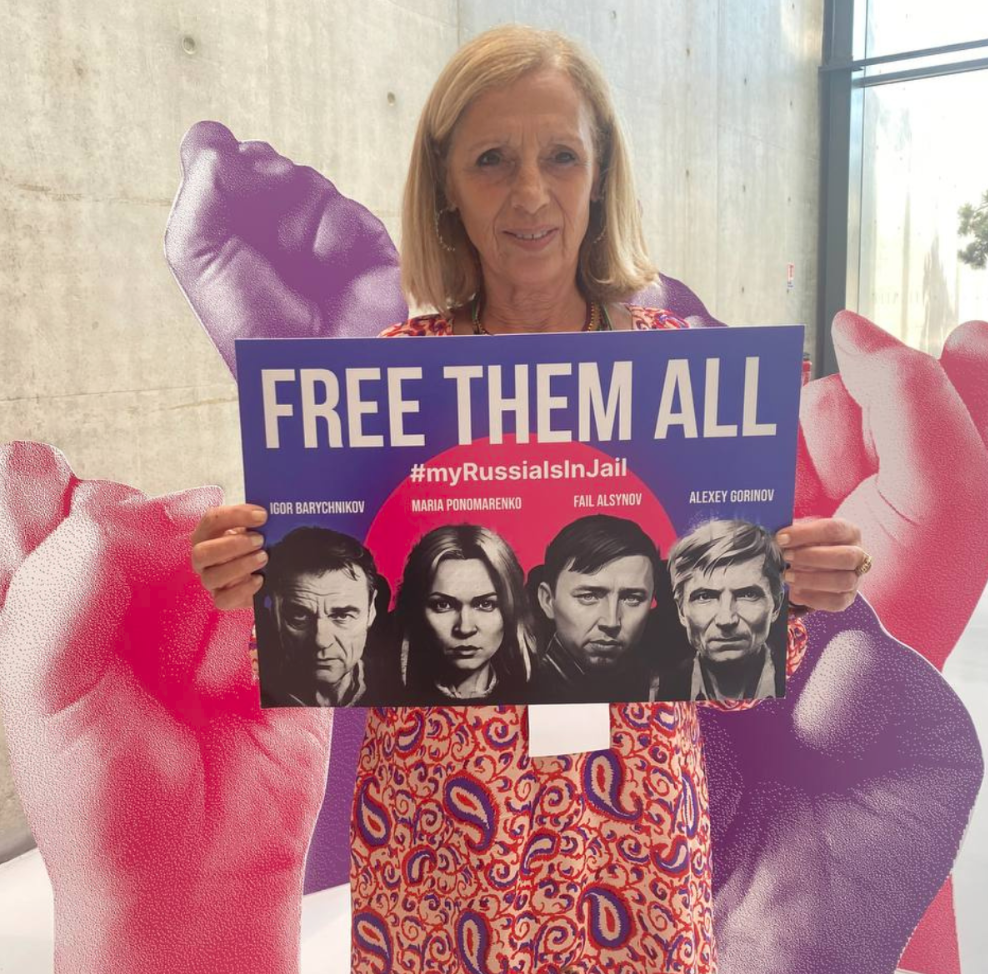

2. Campagne Free Them All

- Objectif : soutien aux prisonnier·es politiques russes

- Activités : une campagne omnicanal pour renforcer le plaidoyer et le soutien directe : collecte de fonds (2 273 €), campagnes médiatiques, plaidoyer auprès des décideurs européens, reels sur les réseaux sociaux et publications

- Partenaires : MEPs, Ville de Paris, Amnesty, médias

- Résultats : soutien direct aux familles et bénéficiaires, visibilité européenne accrue

La campagne Free Them All constitue une action globale de soutien aux prisonniers politiques en Russie et de mobilisation internationale autour de leur situation. Lancée en 2024 et présentée pour la première fois lors de la Conférence du Comité russe contre la guerre en novembre 2024, la campagne a rapidement trouvé un écho auprès des acteurs de la société civile européenne, soulignant à la fois l’urgence de la question et la nécessité d’une action coordonnée.

La campagne repose sur trois piliers complémentaires. Le premier est un dispositif de soutien matériel et juridique, visant à apporter une aide concrète aux prisonniers politiques et à leurs familles : assistance juridique, correspondance, soutien logistique et ressources essentielles pour les personnes détenues en raison de leur opposition au Kremlin ou à la guerre menée contre l’Ukraine. À ce jour, des fonds ont été alloués à cinq bénéficiaires originaires de la République des Komis, à un mineur, ainsi qu’aux jursites du projet Avtozak live, pour un montant total de 2 273 €. La difficulté a consisté à reverser ses fonds pour couvrir directement les frais des familles sans les mettre en danger.

Le deuxième pilier est une campagne médiatique stratégique, fondée sur la diffusion de témoignages, de récits individuels et de mises à jour régulières, afin de sensibiliser les publics internationaux et de mobiliser l’opinion publique autour du sort des prisonnier·es politiques.

Enfin, le troisième pilier repose sur un travail de plaidoyer direct auprès des décideurs politiques français et européens, des élus et de personnalités publiques. L’objectif est de défendre la libération immédiate et inconditionnelle des prisonniers politiques et d’inscrire durablement cette question dans les agendas européens des droits humains.

La campagne a bénéficié d’un soutien politique et institutionnel fort, notamment de la part de plusieurs députés au Parlement européen — parmi lesquels Raphaël Glucksmann, Nathalie Loiseau, Chloé Ridel et Andrey Kovatchev — ainsi que de personnalités publiques et politiques telles que Benjamin Haddad, ministre délégué chargé de l’Europe, le groupe Les Indépendants – Sénat, des membres du Parti socialiste français, et du Conseil de Paris. Ce large soutien a considérablement renforcé la visibilité et l’impact de la campagne à l’échelle européenne.

En combinant aide matérielle, visibilité publique et action politique, Free Them All soutient concrètement les personnes détenues tout en s’inscrivant dans un mouvement global pour la démocratie et la responsabilité en Russie.

Voir toutes les photos de soutien à la campagne

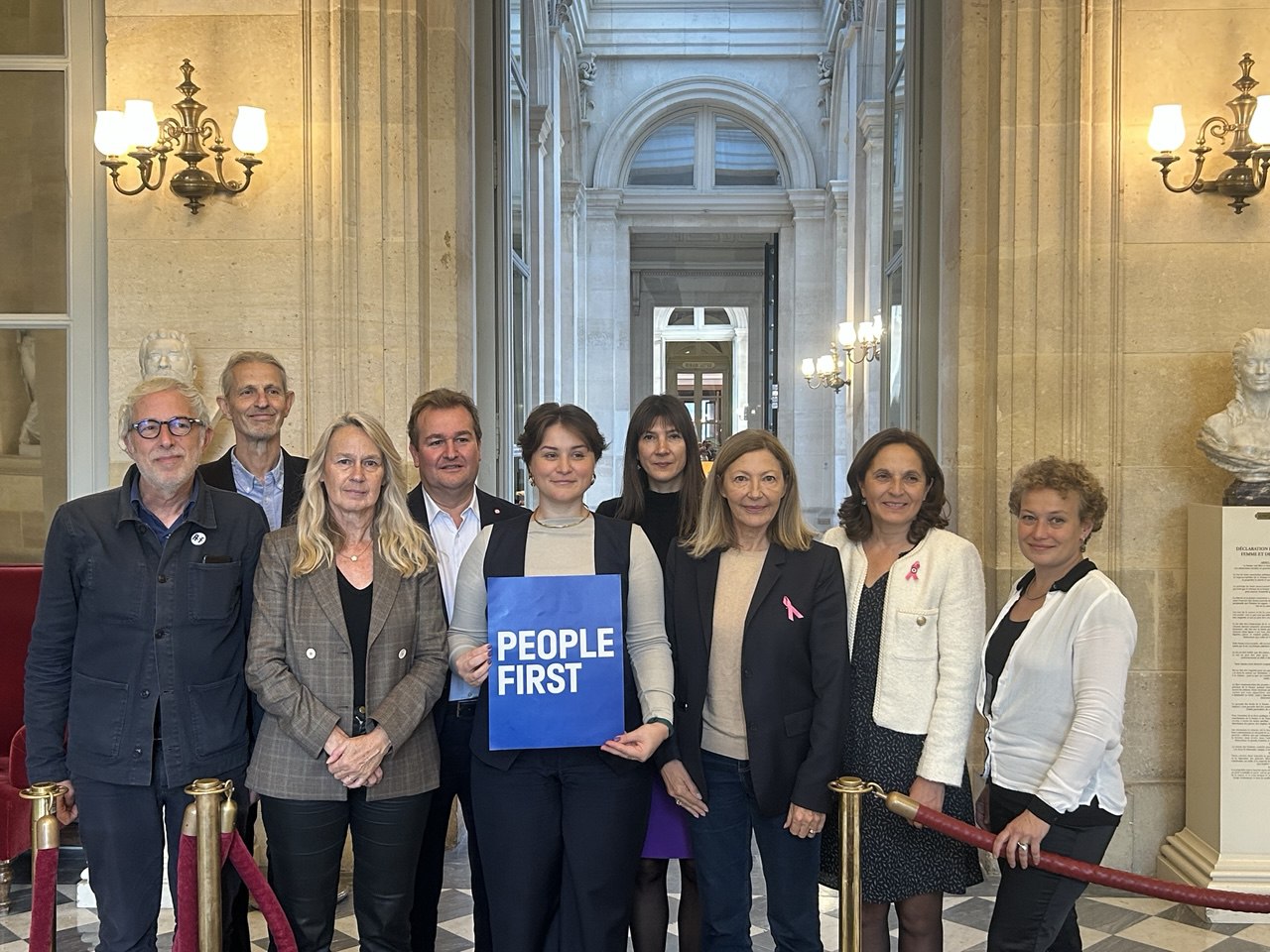

3. People First / Sauver les enfants du poutinisme

- Objectif : inclusion des prisonniers politiques russes, civils et enfants ukrainiens dans les négociations de paix

- Activités : plaidoyer transnational, conférences

- Résultats : renforcement du réseau européen de défense des droits humains, plateforme unifiée pour le plaidoyer

Dans le cadre de l’initiative, Russie-Libertés a mené en 2025 une action transversale en faveur de la protection des populations les plus vulnérables affectées par la guerre, en particulier les enfants, les prisonniers civils et les prisonniers politiques.

Un axe central de ce travail a été la campagne People First, qui plaide pour l’inclusion, dans toute perspective de négociation de paix, des prisonniers politiques russes, des civils ukrainiens détenus en Russie, des prisonniers de guerre, ainsi que des enfants ukrainiens déportés de force. Cette campagne est portée conjointement par des défenseurs des droits humains ukrainiens et russes et se déploie à l’échelle intertnationale, en étroite collaboration avec des organisations de la société civile dans plusieurs pays.

Grâce à des actions de plaidoyer coordonnées, des lettres ouvertes et des initiatives communes, cette dynamique a permis de renforcer une plateforme collective en faveur de la justice, de la responsabilité et de la protection humanitaire dans les débats internationaux.

Dans ce cadre, la directrice de Russie-Libertés, Olga Prokopieva, est intervenue à La Fabrique de la Diplomatie à Paris, un événement de référence consacré aux enjeux diplomatiques contemporains. La table ronde « Médiation et paix : le rôle des acteurs non étatiques dans la libération des enfants ukrainiens » a réuni des représentant·es de la société civile française, ukrainienne et russe, ainsi que des experts internationaux, afin de réfléchir aux stratégies de protection et de libération des enfants déportés. Cette participation a souligné la dimension transnationale de la campagne et renforcé le rôle des acteurs de la société civile dans le plaidoyer humanitaire à l’échelle européenne.

Et Sasha Romantsova, directrice exécutive du Centre pour les Libertés Civiles, est intervenue au nom de la campagne lors du Forum de l’association. Une réunion a également été organisée avec Sasha et des députées français à l’Assemblée Nationale.

4. Coalition LGBTQ+ / Festival Queer russe

- Objectif : soutenir la communauté LGBTQ+ russe en exil et promouvoir la solidarité internationale

- Activités : festival (200+ participants), panels thématiques, ateliers, projections de films, soutien psychologique et juridique

- Résultats : mise en réseau des acteurs européens et russes, visibilité médiatique, campagnes de solidarité

En 2025, Russie-Libertés a engagé un processus structurant visant à la création d’une coalition européenne LGBTQ+, destinée à coordonner les efforts d’organisations russes et européennes soutenant les personnes queer confrontées à des régimes autoritaires ou vivant en exil.

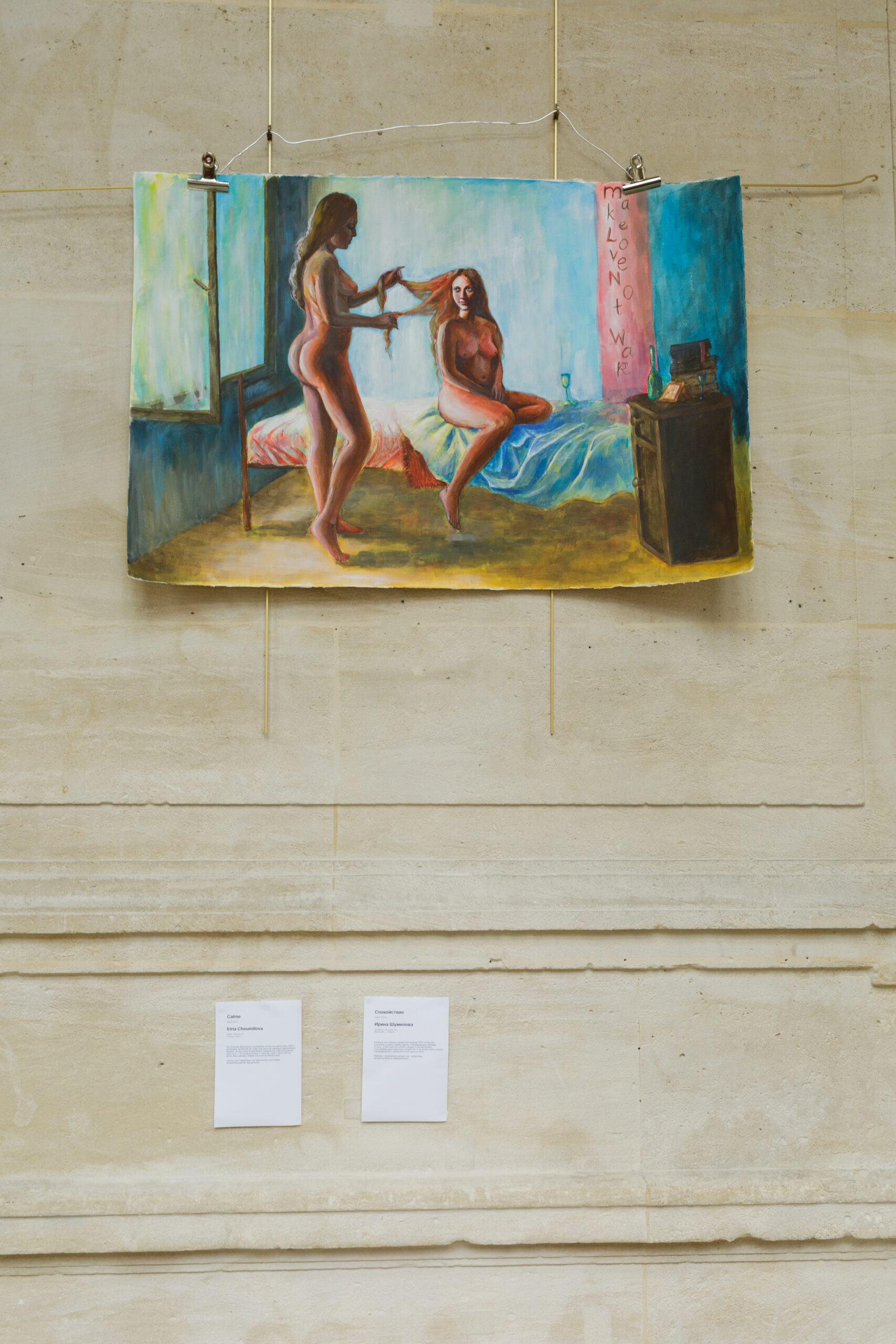

Une étape clé de cette dynamique a été le Festival queer russe, organisé à Paris du 25 au 27 juin 2025. L’événement a rassemblé plus de 200 participants — artistes, militants, personnes exilées et alliés — autour de trois jours de spectacles, expositions, projections, ateliers et tables rondes. Le festival a été organisé par Russie-Libertés, Espace Libertés | Reforum Space Paris et Centre T, avec le soutien de la Ville de Paris, de la Mairie du 11ᵉ arrondissement et d’Inter-LGBT. Le festival a constitué un espace de convergence inédit pour les acteurs de la société civile, favorisant la coordination des initiatives, le partage d’expériences et le renforcement des réseaux. Plus de 120 œuvres artistiques — arts visuels, photographie, vidéo, musique et performance — ont été présentées par plus de 70 artistes et activistes, illustrant le rôle central de la création artistique comme forme de résistance. Quatre tables rondes thématiques ont abordé des enjeux majeurs : les réalités de la vie queer en Russie, les formes de résistance en contexte autoritaire, l’expérience de l’exil et les solidarités internationales, avec des perspectives venues notamment d’Iran, de Turquie et de la communauté ouïghoure.

Le festival a également mis en lumière des initiatives concrètes de soutien aux personnes LGBTQ+ en exil. Quatre initatives— CaVa, Centre T, EQUAL PostOst et Espace Libertés — ont présenté leurs programmes d’aide juridique, de soutien psychosocial, d’hébergement d’urgence, d’accompagnement à l’intégration et de soutien à la création artistique.

Dans ce cadre, Russie-Libertés poursuit également un accompagnement psychologique régulier des personnes LGBTQ+, tandis que les évacuations d’urgence sont coordonnées avec des organisations partenaires de défense des droits humains, en lien avec le ministère français de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères.

L’action phare de fin d’année de la coalition a été une campagne de solidarité conjointe avec Amnesty International France, organisée le 30 novembre 2025, à l’occasion des deux ans de la désignation officielle des organisations LGBTQ+ en Russie comme « extrémistes ». Cette mobilisation, combinant rassemblement public et campagne médiatique, a permis de renforcer le soutien international à la communauté LGBTQ+ russe et de rappeler la persistance de la répression.

5. Espace Libertés

- Objectif : Soutenir et structurer la société civile russophone en exil en France.

- Activités : Accueil de 450+ résidents; 785+ consultations juridiques; 404+ consultations psychologiques et 20+ sessions de groupe; 150+ événements publics et communautaires.

- Résultats : Hub central de la société civile russe en exil, renforcement des capacités individuelles et collectives, pérennisation du centre jusqu’en 2026.

En 2025, Espace Libertés a poursuivi son développement en tant que principal espace de référence pour la communauté russophone anti-guerre et en exil en France. Le Centre a rassemblé plus de 500 résidents réguliers — militants, journalistes, artistes, chercheurs et défenseurs des droits humains — et s’est imposé comme un lieu clé de soutien civique, juridique, psychosocial, culturel et communautaire.

Le Centre a accueilli de nombreuses rencontres avec des figures majeures de la société civile russe, parmi lesquelles Vladimir Kara-Murza, Lev Ponomarev, Lana Pylaeva, Ilya Yashin, Vadim Prokhorov et Sergey Parkhomenko. Ces échanges ont porté sur les droits humains, la résistance politique, le rôle des médias indépendants et les stratégies de survie civique sous régime autoritaire.

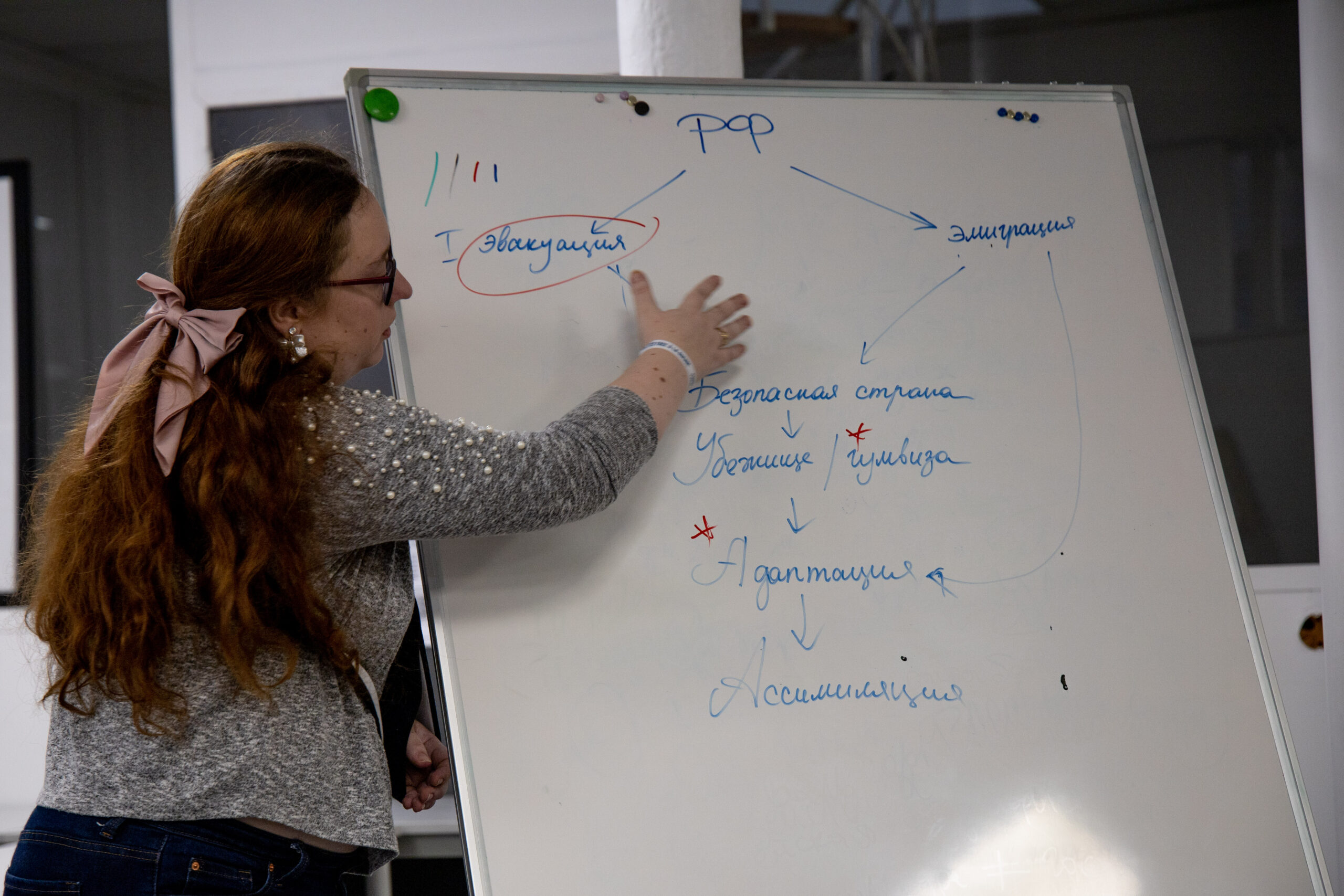

Des ateliers sur des questions administratives et juridiques clés pour des émigrés ont également enrichi le programme.

Enfin, l’Espace Libertés fonctionne comme un véritable espace communautaire vivant, accueillant 2 à 5 événements par semaine, initiés par les résident·es, leaders communautaires et organisations partenaires, favorisant l’entraide, la coopération et la résilience collective.

6. Platforma – Support to Anti-War Initiatives

- Objectif : renforcer et unifier le mouvement anti-guerre russe

- Activités :

- Congrès annuel à Bruxelles (8–9 avril)

- Groupes de travail thématiques et policy papers : déserteurs, désinformation, rhétorique anti-genre, normalisation de l’autoritarisme, etc

- Création d’une stratégie pour le mouvement civique démocratique russe

- Plaidoyer international (États-Unis et Europe)

- Renforcement du dialogue au sein de la société civile : série de rencontres en-ligne intitulées “Discussions importantes”

- Résultats : réseau européen renforcé, dialogue international, renforcement capacités organisationnelles des initiatives

En 2025, Russie-Libertés a joué un rôle actif au sein de la Plateforme des initiatives civiques et anti-guerre une alliance internationale réunissant plus de 100 organisations de la société civile russe et russophone engagées contre la guerre. Dans ce cadre, l’association a contribué à l’initiative “Soutien aux initiatives anti-guerre”, visant à renforcer les capacités collectives du mouvement anti-guerre russe, à promouvoir les droits humains et à répondre aux conséquences humaines, sociales et politiques de la guerre menée contre l’Ukraine.

Cette dynamique s’inscrit dans un contexte de forte fragmentation du mouvement anti-guerre russe, marqué par la répression, l’exil forcé et la dispersion géographique. L’action de Platforma vise à recréer des espaces de coordination, de réflexion stratégique et de solidarité internationale, indispensables à la survie et à la visibilité de ces initiatives.

7. Congrès des initiatives civiques et anti-guerre – Bruxelles

Les 8 et 9 avril 2025, Russie-Libertés a coorganisé à Bruxelles le Congrès des initiatives civiques, anti-guerre et humanitaires russes, aux côtés d’autres organisations membres de Platforma, avec le soutien de l’Union européenne et du ministère allemand des Affaires étrangères.

Cet événement majeur a réuni plus de 300 participants venus de Russie, de l’Union européenne, d’Ukraine, du Caucase du Sud, d’Asie centrale et des États-Unis : militants, défenseurs des droits humains, représentants d’initiatives citoyennes, personnalités publiques et politiques russes et européennes, ainsi que des représentants d’institutions européennes.

Le congrès a permis d’évaluer les avancées des initiatives anti-guerre et humanitaires, d’élaborer des stratégies communes, de renforcer les capacités de plaidoyer et d’accroître la visibilité internationale du mouvement anti-guerre russe. Des tables rondes, groupes de travail et expositions ont favorisé le partage de bonnes pratiques, le développement de projets conjoints et la mise en lumière d’initiatives de terrain.

Dans ce cadre, Russie-Libertés a également accueilli 15 jeunes militants venus de France et d’autres pays européens, bénéficiant d’un programme spécifique de cinq jours consacré à la découverte des institutions européennes, aux rencontres avec des acteurs clés de la société civile et au renforcement des liens transnationaux autour des valeurs de paix, de solidarité et de démocratie.

8. Mobilisation citoyenne et engagement communautaire

Tout au long de l’année 2025, Russie-Libertés a organisé et soutenu de nombreuses actions d’engagement civique visant à mobiliser les citoyens, sensibiliser aux enjeux politiques et sociaux liés à la guerre, et soutenir les défenseurs des droits humains.

En février 2025, en partenariat avec le Comité anti-guerre de Russie, l’association a organisé à l’Hôtel de Ville de Paris la conférence « Libération des prisonniers ukrainiens en Russie : coopération, plaidoyer et soutien ». Cet événement a mis en lumière la situation des civils ukrainiens détenus en Russie et des enfants déportés de force, ainsi que la coopération entre défenseurs des droits humains ukrainiens et russes pour leur venir en aide. Parmi les intervenants figuraient Evguenia Tchirikova (Activatica), Anastasia Shevchenko (Through the Wall), Mikhail Savva (Center for Civil Liberties) et Stas Doutov (ancien prisonnier de guerre ukrainien), qui ont partagé leurs analyses des conditions de détention et des stratégies de plaidoyer. La conférence a également mis en exergue la campagne People First et a contribué à renforcer les coopérations européennes entre organisations de la société civile, avec le soutien de la Ville de Paris. Des rencontres ont pu être organisées entre les intervenants et des représentants des institutions françaises.

Le 23 février 2025, Russie-Libertés a été partenaire officiel de la manifestation Marche pour l’Ukraine à Paris, organisée à l’occasion du troisième anniversaire de l’invasion à grande échelle de l’Ukraine par la Russie. Plus de 10 000 personnes se sont rassemblées place de la République avant de défiler jusqu’à la place de la Bastille pour exprimer leur solidarité avec l’Ukraine et appeler à un renforcement du soutien international.

Au cours de l’année, l’association a également organisé à Paris, place du Louvre, l’exposition internationale « Faces of Russian Resistance ». Cette exposition a donné à voir les parcours de celles et ceux qui s’opposent au régime de Vladimir Poutine et à la guerre, en rappelant notamment la situation de plus de 1 500 prisonniers politiques en Russie. L’inauguration s’est tenue en présence de Vladimir Kara-Murza, de députés français, de l’ambassadrice du Canada en Russie et de défenseurs des droits humains. L’exposition a été suivie d’une installation dédiée à Alexeï Navalny et accompagnée d’une collecte de dons dans le cadre de la campagne Free Them All, destinée à soutenir les prisonniers politiques et leurs familles.

9. Plaidoyer et action politique

Parallèlement, Russie-Libertés a mené un travail soutenu de plaidoyer à l’échelle internationale. Parmi les principales actions de plaidoyer menées en 2025 figurent : des rencontres entre des figures de la société civile russe et des responsables politiques, des institutions publiques et des réseaux de défense des droits humains français et européens: Vladimir Kara-Murza, Vladimir Milov, Zhanna Nemtsova, Ilya Yashin, des membres du Comité anti-guerre de Russie. Ces rencontres ont contribué à une meilleure compréhension de la situation en Russie et ont mené à des décisions pour une meilleure résilience de la société civile russe, pour l’amélioration de l’efficacité des sanctions, et pour le soutien à la jeunesse de Russie.

Le 3 juin 2025, la directrice exécutive de Russie-Libertés est intervenue à une Table ronde au Parlement européen : « No Return to Repression: Protecting Russian Anti-War and LGBTQI Activists in Europe », organisée par les eurodéputés Sergey Lagodinsky et Andrey Kovatchev, en présence de l’ancien prisonnier politique Ilya Yashin. Olga Prokopieva a exposé les difficultés rencontrées par les militant·es anti-guerre et LGBTQI russes dans leur recherche de protection au sein de l’Union européenne, appelant à une volonté politique renforcée pour garantir leur sécurité et leur intégration. Parallèlement, des rencontres individuelles ont été organisées avec plusieurs eurodéputés et responsables politiques : Nathalie Loiseau, Raphaël Glucksmann, Chloé Ridel, Sergey Lagodinsky, Sebastian Tynkkynen, Andrey Kovatchev et Bernard Guetta.

Russie-Libertés demeure un acteur clé et un interlocuteur privilégié entre la société civile russe et les responsables politiques français et européens, facilitant le dialogue, le plaidoyer et la coordination des actions.

10. Soutien juridique et administratif / assistance humanitaire

Assuré par une équipe experte : une avocate, une juriste et deux bénévoles.

Objectif : sécuriser visas, asile et intégration des exilé·es

- Activités : consultations juridiques, renouvellements APS, accompagnement des déserteurs

- Résultats : 290 dossiers traités (visas humanitaires, visas talents et autres types de visas, APS, asile et autres consultations juridiques et administratives).

Russie-Libertés joue un rôle central dans l’accueil et l’intégration de ressortissants russes menacés en raison de la répression politique consécutive à l’invasion de l’Ukraine. En étroite collaboration avec les autorités françaises et un réseau d’associations partenaires, l’association assure un accompagnement juridique et administratif personnalisé, de la mise en sécurité d’urgence jusqu’au suivi à long terme. Des situations particulièrement complexes sont débloquées grâce à l’intervention de Russie-Libertés.

Parmi les situations accompagnées figurent notamment :

- des artistes, écrivains, chercheurs poursuivis pour leurs activités publiques, culturelles ou académiques ;

- des familles de réfugiés politiques confrontées à des procédures de regroupement familial longues et complexes ;

- des militants anti-guerre et défenseurs des droits humains en situation de rétention ou menacés d’expulsion vers la Russie (États-Unis, Caucase, Asie centrale) ;

- des déserteurs de l’armée russe poursuivis pénalement pour leur refus de participer à la guerre.

11. Soutien aux médias indépendants / lutte contre la propagande

- Objectif : soutenir l’information indépendante russe et francophone

- Activités : studio Espace Libertés (150+ projets), collaborations Novaya Gazeta Europe, lancement Info Most

- Résultats : renforcement de l’accès à l’information pour publics russophones et francophones

En 2025, Russie-Libertés poursuit activement son engagement contre la propagande du Kremlin en soutenant les médias russes indépendants en exil et en contribuant à la circulation d’une information fiable et vérifiée.

Le studio d’Espace Libertés a accompagné plus de 150 projets médiatiques, permettant à des rédactions russophones de produire et de diffuser des contenus à destination du public en Russie, malgré la censure et la répression. Ces actions ont renforcé la capacité des médias indépendants à maintenir un lien avec leurs audiences et à documenter la réalité politique, sociale et humanitaire.

Russie-Libertés collabore notamment avec des médias reconnus tels que Novaya Gazeta Europe et prépare le lancement d’une nouvelle initiative conjointe, Info Most, destinée aux publics francophones en Europe — en particulier en France, en Belgique et en Suisse — ainsi qu’au Canada. Il s’agit d’une newsletter et d’une plateforme d’information proposant des analyses d’experts et de journalistes en exil, des décryptages contextuels de l’actualité russe et régionale, ainsi que des contenus permettant de lutter contre la désinformation.

Parallèlement, l’association entretient une coordination régulière avec des médias russes et français, soutenant les journalistes en exil et amplifiant les enquêtes indépendantes sur la répression politique, les violations des droits humains et la guerre contre l’Ukraine.

12. Projet Culture et Résistance Anti-Guerre

En 2025, Russie-Libertés a développé une activité culturelle active pour soutenir la résistance anti-guerre et donner une visibilité aux voix dissidentes de la société civile russe. Parmi les actions principales:

- Forum Russie-Libertés : l’artiste Monetоchка a été invitée à se produire lors du Forum, combinant panel et performance, afin de montrer comment l’art peut être un vecteur d’expression civique et de solidarité.

- Expositions artistiques :

- Artists Against Kremlin : présentée dans le cadre du Congrès de Platforma à Bruxelles, cette exposition a permis de valoriser le travail d’artistes russes opposés à la guerre et de sensibiliser un public européen aux enjeux de répression et de liberté d’expression.

- La Russie contestataire de Nikita Mouraviev : exposition photographique documentant la résistance civile et les manifestations anti-guerre en Russie.

13. Soutien à la société civile en Russie

- Organisation de sessions fermées et études sur la société civile russe

- Suivi des initiatives locales et maintien de la visibilité internationale

En complément de l’accompagnement des personnes persécutées cherchant protection à l’étranger, Russie-Libertés mène des actions ciblées en soutien à la société civile restée en Russie : présentations et rencontres confidentielles à destination de chercheurs, décideurs politiques et défenseurs des droits humains français. Ces initiatives ont permis d’alimenter la réflexion européenne sur les dynamiques internes de résistance et les formes d’engagement civique sous autoritarisme.

Ces actions garantissent que, malgré l’intensification de la répression, la société civile russe conserve une visibilité internationale, un appui stratégique et des opportunités de coopération.

2025 en chiffres

- 4 manifestations organisées ou coorganisées en France et en Europe

- 450+ résidents réguliers d’Espace Libertés | Reforum Space Paris

- 40+ événements organisés

- 15+ participations à des conférences et événements internationaux

- 300+ participants au Forum annuel Russie-Libertés

- 400+ lettres envoyées à des prisonniers politiques

- 3 conférences internationales organisées

- 101 000 vues mensuelles sur les réseaux sociaux

- 4 campagnes de collecte de fonds

- 290 demandes d’aides traitées (visas humanitaires, asile, titres de séjour etc)

- 1 100+ participants uniques aux événements

- 15+ apparitions médiatiques dans la presse française et internationale

- 12 000+ abonnés sur les réseaux sociaux

- 13 notes, lettres ouvertes et tribunes publiées sur le site internet et sur les réseaux sociaux

Notes et lettres ouvertes écrites ou co-écrites par Russie-Libertés en français

Résultats et impact

À la fin de l’année 2025, Russie-Libertés a atteint des résultats concrets, mesurables et durables dans l’ensemble de ses axes stratégiques : soutien communautaire, plaidoyer, action médiatique et renforcement institutionnel.

Plaidoyer et sensibilisation

Russie-Libertés s’est imposée comme une voix européenne de référence du mouvement démocratique russe, en organisant ou coorganisant trois grandes conférences internationales et en participant à 15+ événements institutionnels, notamment à l’Assemblée nationale française et au Parlement européen. Les campagnes Free Them All et People First ont obtenu le soutien d’élu·es européens, d’institutions françaises et de collectivités locales.

En 2025, Russie-Libertés a publié et présenté six rapports et notes de synthèse. L’association a également diffusé trois lettres ouvertes : la première concernait les négociations entre Trump et Poutine en Alaska, la deuxième soutenait la campagne People First, et la troisième appelait la communauté internationale à réagir lors de la visite en Suisse de la délégation du Kremlin.

De plus, nous avons pu obtenir 2 votes du Conseil de Paris : un vote pour une plaque commémorative en l’honneur de Boris Nemtsov et un autre, en soutien à la communauté LGBTQ+ de Russie.

Présence médiatique

En 2025, l’association a été citée dans plus de 15 médias français et internationaux, touchant plus de 10 millions de personnes. L’audience sur les réseaux sociaux a fortement progressé (Instagram +35 %, Facebook +27 %, plus de 100 000 vues mensuelles). Expositions, campagnes et le documentaire Politzek ont renforcé la visibilité internationale des prisonniers politiques, des activistes, journalistes et artistes en exil.

Mobilisation culturelle et civique

Russie-Libertés a mobilisé l’art et la culture comme outils de résistance et de reconstruction collective. Le Festival Queer russe, les performances d’artistes engagés et le Forum Russie-Libertés ont favorisé le dialogue entre sociétés civiles russe et européenne et renforcé l’engagement citoyen.

Pérennité institutionnelle

Malgré un contexte de baisse des financements internationaux, l’association a consolidé sa résilience opérationnelle, obtenant des subventions diverses, publiques et privées, et ainsi assurant la continuité de nos projets jusqu’en 2026.

La diversification des ressources, la structuration du bénévolat et l’implication active de membres du Conseil d’Administration ont contribué à la durabilité et à l’impact de notre action.

Perspectives 2026

Forte des acquis de 2025, Russie-Libertés engage une nouvelle phase stratégique, marquée par le passage de la réponse d’urgence à un renforcement structurel de ses activités.

En 2026, Russie-Libertés intensifiera son cœur de mission qui est la sensibilisation du public et des autorités françaises et européennes sur la situation en Russie, le plaidoyer pour une paix juste et durable pour l’Ukraine, pour la libération des prisonniers politiques et de tous les otages de la guerre.

De plus, l’association poursuivra le développement de l’aide aux membres de la société civile exilée par le biais de l’activité de son Espace Libertés | Reforum Space Paris : espaces de coworking, studio d’enregistrement et pôle juridique renforcés. Les services psychologiques seront étendus grâce à de nouveaux partenariats et programmes de formation, avec l’ambition de faire du centre un modèle européen de résilience civique en exil. L’accompagnement vers l’intégration professionnelle sera une des priorités de l’Espace en 2026.

L’association renforcera également sa diplomatie culturelle avec des événements qui mettront en valeur la culture russe engagée.

Le soutien aux populations vulnérables se traduira notamment par des événements thématiques et des publications sur la situation des personnes LGBTQI+, des enfants, des femmes.

La lutte contre la désinformation et la propagande sera développée avec le lancement d’Info Most, plateforme médiatique coproduite avec des journalistes en exil, ainsi que de projets de coopération avec des journalistes européens.

Enfin, Russie-Libertés poursuivra la diversification de ses financements à travers des partenariats pluriannuels avec des fondations européennes et des ONG internationales, garantissant stabilité et impact à long terme.